knowing how it all started

There is a plausible explanation for the existence of money. According to legend, before money, we all had to barter for the commodities we desired. I needed to locate someone who wanted chickens and had extra wheat if I wanted wheat and had chickens. Money addresses the problem of “double coincidence” by allowing me to sell my hens in order to purchase your wheat. We’d invent it right away if we didn’t have any money.

The issue with this simple narrative is that it may or may not be accurate. According to anthropologists, there has never existed a pure barter economy. Central planning, informal gift economies, and IOUs denominated in cows were some of the ways pre-money economies were structured.

The classic by Sir Jon Hicks Money is filled with a Market Theory of Money

. Hicks was a key player in twentieth-century economics who received a Nobel Prize, and here, at long last, is a simple tale that explains why we have banks at all. I’m still not convinced that this account is historically founded – or that we can comprehend what a modern bank does, or should do, by historical analogy – but it does give a better history than barter.

With that warning caveat in mind, here is Hicks’ banking story. He starts in a world where money is already the most common method of payment and divides a transaction into three parts:

The buyer and seller agree on what will be sold and at what price.

The products are delivered by the buyer.

The payer is the one who makes the payment.

Step 1 must be completed first, although payment and delivery can occur in any order after that, depending on the parties’ agreement. Credit bridges the gap between contracting and payment. Credit is a centuries-old concept that is essential to modern economies. According to Hicks, “paying on the spot” is the exception rather than the rule, at least for orders of a particular size:

I can buy a newspaper on the spot as I go down the street, or I can have a copy delivered to my house every morning by a newsagent. I shouldn’t pay for each issue as soon as I get it; instead, I should wait until the end of the month, when he sends in his payment.

… It’s undoubtedly true that the spot mode of payment is usually used exclusively for little transactions – tiny from the perspective of one or both of the parties involved. People do not, and never have been, in the habit of carrying around enough cash or notes to pay for a home or furnish it.

The crucial point is that credit is usual, not exceptional. We have been provided credit every time we pay a bill – whether at a restaurant or for a credit card.

Debt exists between contracting and payment, and debt is quantified in money (at least on the buyer’s side; debt is measured in products on the seller’s side).

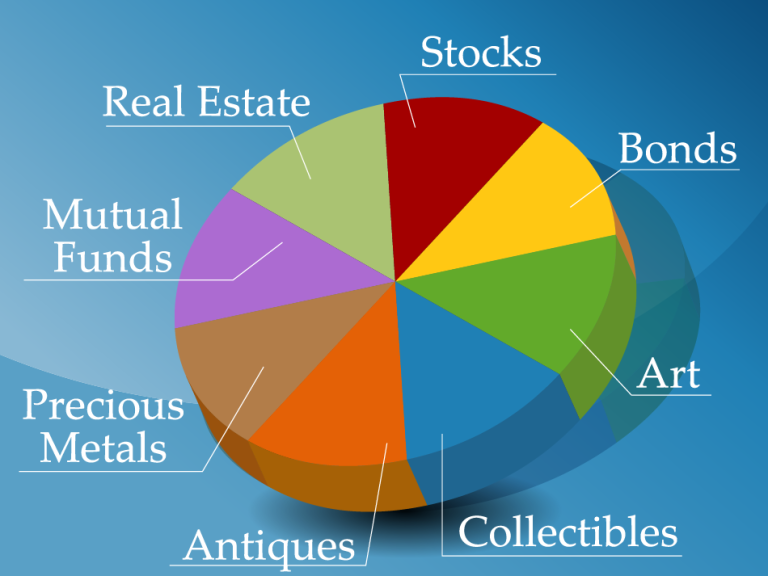

Money has long been a source of debate regarding what it is and, more importantly, what it accomplishes, but in a credit-based economy, it serves two distinct functions:

As a result, it appears that money has just two distinct functions: standard of value and medium of exchange. Is one implying the other, or are they independent? It’s difficult to understand how a debt indicated in money can be paid unless money is implicit in the debt to be paid. As a result, money as a medium of exchange implies money as a unit of measurement. Is it possible, however, to discharge an obligation that is stated in money in a different way? It’s a possibility.

The myth of the barter trade

Consider what life was like before money. Let’s say you cooked bread but didn’t have any meat.

But what if the butcher in town isn’t interested in your bread? You’d have to track out someone who did and trade with them until you had some meat.

It’s easy to see how this becomes extremely difficult and inefficient, which is why humans created money in the first place: to make it easier to exchange products. Right?

This ancient world of barter appears to be rather troublesome. It might also be entirely made up.

Adam Smith, the 18th-century Scottish philosopher who is credited with establishing modern economic theory, popularized the concept that barter was a forerunner to money. He recounts a fictional situation in The Wealth of Nations in which a baker living before the advent of money wanted a butcher’s meat but couldn’t afford it.

According to Smith, such a condition was so unpleasant that cultures had to invent money to enable commerce. Similar principles were proposed by Aristotle, and they are currently found in almost every basic economics textbook. One states, “In primitive, early economies, individuals engaged in barter.” (“The American Indian with a pony to sell had to wait until he found another Indian who wanted a pony and was able and ready to trade it in exchange for a blanket or other item that he needed,” read one previously.)

However, anthropologists have noted that this barter economy has never been observed during study trips to less developed parts of the world. “Pure and simple, there is no example of a barter economy

“Nothing like it has ever been reported, let alone the development of money from it,” stated Caroline Humphrey, a Cambridge anthropology professor, in a 1985 study. “All known ethnography indicates that such a thing never existed.”

Humphrey isn’t the only one who feels this way. Similar arguments have long been advanced by other scholars, notably the French sociologist Marcel Mauss and the Cambridge political economist Geoffrey Ingham.

When barter first began, it wasn’t as part of a strictly barter system, and it didn’t come from money—it came from money. After Rome collapsed, for example, Europeans utilized barter to replace the Roman coinage that they had grown accustomed to. “In most of the situations we’re aware of, [barter] takes place between people who are comfortable with the use of money, but in one example, [barter] takes place between people who are unfamiliar with the use of money.”

but don’t have a lot of stuff about for one reason or another,” says David Graeber, an anthropology professor at the London School of Economics.

So, what happened if barter didn’t exist? Anthropologists describe a broad range of transaction systems, none of which involve “two cows for ten bushels of wheat.”

Longhouses, for example, were used by Iroquois Native Americans to store their possessions. According to Graeber, the items were subsequently distributed by female councils. Other indigenous groups had “gift economies,” which worked like this: If you were a baker in need of meat, you didn’t trade your bagels in exchange for the butcher’s steaks. Instead, you persuaded your wife to inform the butcher’s wife that the two of you were iron-deficient, and she’d respond with something like “Oh really?” Get a hamburger, we have plenty!” You’d help the butcher out if he needed a birthday cake or assistance relocating to a new apartment down the road.

According to the barter myth, people have always had a quid pro quo, exchange-based worldview.

On the surface, this seems a lot like delayed barter, but there are some key distinctions. For one thing, it’s far more efficient than Smith’s barter system, because it doesn’t rely on each person possessing what the other wants at the same time. It’s also not tit for tat: no one ever sets a monetary value to steak, cake, or construction labor, so debts can’t be transferred.

Exchange isn’t impersonal in a gift economy. If you’re trading with someone you care about, it’s a good idea, to be honest.

According to Graeber, you’ll “inevitably care about her enough to take her specific wants, desires, and situation into account.” “Even if you do trade one thing for another, you’re probably going to frame it as a present.”

Non-monetary societies did have trade, but not among villagers. Instead, it was almost exclusively used with strangers or even enemies, and it was frequently accompanied by elaborate ceremonies including commerce, dancing, feasting, fake battle, or sex—and occasionally all of these things at the same time. In the 1940s, anthropologist Ronald Berndt observed the indigenous Gunwinggu people of Australia:

Men from the visiting moiety sit peacefully as women from the opposing moiety approach them, offer them cloth, strike them, and invite them to copulate.

, despite the fact that the narrative is well-known in economics courses and among the general public. Some contend that no one really thought barter was genuine in the first place—that the concept was only a primitive model for simplifying the framework of current economic systems, rather than a true theory about historical ones.

Michael Beggs, a lecturer in political economics at the University of Sydney, told me, “I don’t think anyone believes there was ever a historical reality, even the economists producing the textbook.” “It’s more of a mental exercise.”

Nonetheless, Adam Smith seems to believe in barter. “When the division of labor first began to take place, this power of exchanging must frequently have been very much clogged and embarrassed in its operations,” he writes, before going on to say, “When the division of labor first began to take place, this power of exchanging must frequently have been very much clogged and embarrassed in its operations.”

“, followed by a description of barter’s inefficiencies. And, according to Beggs, many textbooks appear to sloppily embrace this stance. He continues, “They sort of utilize that fairy tale.”

Part of the difficulty in picturing a world without money stems from the fact that money has existed for such a long time. The first Indian money was made out of silver bars and debuted in the sixth century B.C. Around the same period, the world’s first coins arrived in Lydia (modern-day Syria).

However, despite the fact that money has been there for a long time, humans have been around for hundreds of thousands of years longer, and it may be a mistake to believe that current economics represents some type of basic human nature.

“Economic theory must always be historical bound,” argues Beggs. “I believe it is a folly to believe that going back to the roots of money can reveal the workings of current money.” Given how little is known about such a long period of time, he does point out that, while barter may not have been widespread, it’s plausible that it occurred somewhere and resulted in money.

Despite the fact that some anthropologists have long suspected the barter system was little more than a thought experiment, the concept is extremely popular. And this isn’t simply an academic curiosity: the concept of barter may have influenced the course of history.

“The worldview that economics courses are based on… has now become so much a part of our In Debt: The First 5,000 Years, Graeber argues, “We find it difficult to envisage any other feasible arrangement.”

Because barter is essentially a less efficient version of money, Graeber claims that the barter myth indicates that people have always had a type of quid pro quo, exchange-based mentality. When you consider that other, wholly different systems existed, money begins to appear like a choice rather than a natural development of human nature.

For one reason, according to Graeber in Debt, the barter myth “allows us to conceive a universe that is nothing more than a series of cold-blooded calculations.” Even though behavioral economists have presented a compelling case that people are rational, this viewpoint is still widely held.

However, the harm may extend beyond a faulty understanding of human psychology. According to Graeber, if you give precise values to items, as you do in a money-based economy, it’s all too simple to assign value to people, allowing institutions like slavery (where individuals can be bought) and imperialism to flourish (which is made possible by a system that can feed and pay soldiers fighting far from their homes).

Whether or not one agrees with such broad allegations, it’s worth remembering that monetary debt, a result of currency, has been used to influence people on numerous occasions. For example, Thomas Jefferson proposed that the government encourage Native Americans to buy items on credit so that they could

They will be compelled to sell their lands if they go into debt. Debt-collection cases are disproportionately prevalent in black areas today. Debt collection cases are twice as likely in black communities as they are in white neighborhoods, even after income is taken into consideration. In litigation filed between 2008 and 2012, $34 million was confiscated from residents of primarily black areas in St. Louis, with the majority of the money coming from debtors’ salaries. During those years, there was one suit for every four inhabitants in Jennings, a St. Louis suburb.

So, if money is a factor, are there other options to consider? Is a gift economy—one that doesn’t put people in debt and depends on social responsibility and trust—better than a money-based system? Or would individuals simply exploit their neighbors? It’s difficult to respond without witnessing a modern gift economy in operation. Fortunately, modern gift economies do exist. They occur on a modest scale among friends who could lend each other a vacuum cleaner or a cup of flour. There’s also an example of a much larger-scale gift economy, albeit one that isn’t always active: The Rainbow Gathering, an annual celebration in which roughly 10,000 people vow not to bring any money and spend a month in the woods (it rotates between several national forests throughout the country each year). Each day, groups of guests set up “kitchens” where they cook and distribute food to thousands of people for free.

Classical economics may assume that individuals would take advantage of such a system, yet everyone is nourished, and those who don’t cook, among other things, play music, build paths, conduct classes, gather firewood, and act in plays.

It’s one thing to keep a community alive and healthy when everyone is camping in the woods and has agreed to that idea. Imagine a gift economy that allows humanity to construct skyscrapers, create iPhones, install air conditioners in every home, and explore space. (The same may be said for tax collection and managing huge corporations.) We already have gift economies among friends and family, so it’s not an all-or-nothing problem. It’s conceivable to increase it inside tiny towns; it’s just a matter of time, certainly desirable.